|

The Planning Phase of Training and Pre-Functional Area Analysis Work August 22, 2012 By GTI President Chadd Harbaugh  Chadd Harbaugh GTI President (Part three of a multi-part report on redefining law enforcement tactical training) Part One - The Dirty Secret About Most Current Law Enforcement Training Programs INTRODUCTION You have probably heard that effective training is the cornerstone of operational success and through proper training, individual officers, leaders, commanders and units achieve tactical and technical competence that builds confidence and agility. But how do we ensure that training programs build and sustain real capabilities and provide a positive return on our investments into them? Effective training programs require energy, time, financing, facilities, doctrine, material, and various and sundry support from a variety of stakeholders that have a vested interest in the training programs and all of these requirements rely on thorough and effective planning. Under the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (GPRA), federal agencies are required to prepare strategic plans (updated at least every 3 years) and annual performance plans to provide direction for achieving the agency's overall mission. As with anything, some plans are much better than others but as a whole, federal agencies do a far better job preparing plans that state and local agencies. However, there is substantial room for improvement at every level within government. The planning phase begins with a vision of the end-result…what do we want our team to be capable of performing? The answer to this question can be found through conducting a Functional Area Analysis (FAA), coupled with a Concept of Operations (CONOPS) plan, and ultimately conveyed through a Commander's Intent. While the planning phase is the start of the entire training cycle (discussed below), planning and analysis should be continuous. In the planning phase we have to ask basic questions. It may seem like common sense that these questions are asked and answered before any training begins but more often than not, it is not the case. Far too often when we train it is to "check the box" without a thorough analysis as to why and how. We have to ask and answer the following:

To state the obvious, during the planning phase the agency stakeholders identify the need of their agency or their staff. Why do we train? What is the ultimate goal of training? Agencies provide training to officers for one of three reasons; 1) capability development, 2) liability reduction, or 3) other (which includes rewarding past performance and other areas which aren't necessarily directly related to an established need for training).

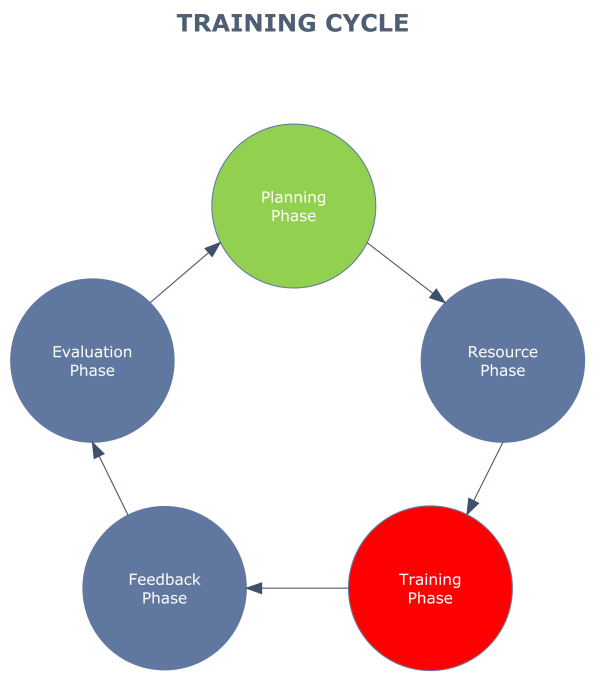

TRAINING CYCLE OVERVIEW There is a cycle involved in any training process; whether it is a recognized formal process or a blind informal process…it is there…always. Trainers tend to lose sight of the cycle as a collective whole and narrowly focus our attention on one to three pieces of the entire cycle that are more directly within their control (planning, training and feedback). Agency planners, commanders and heads, most often focus their attention on other aspects of the training cycle such as resourcing and evaluation (and to a lesser extent, planning). There is often disconnect between the two groups (trainers and agency leaders), and it results in a disservice to the training itself and the agency employing the trainee. All training cycles have a minimum of five phases. The phases are typically completed chronologically but certain aspects of each category should occur continually throughout the entire cycle:

Each phase of the training cycle involves different stakeholders. Some stakeholders should be involved throughout the entire process while others may be involved in only one phase or bounce in and out of involvement throughout the various phases. Even if an individual or a group of stakeholders is not involved throughout the entire process, the entire process affects all of the stakeholders. Stakeholder involvement is crucial for program success (see stakeholder involvement heading later in this article). PROBLEMS WITH CURRENT TRAINING SYSTEMS As mentioned in the last two newsletters, the current training model for most law enforcement jurisdictions is far from ideal and issues are clearly visible in every phase of the training cycle. These issues affect our ability to produce true capabilities; expose agencies, supervisors, leaders and personnel to potential liability issues and added risk; and in many cases are fiscally irresponsible. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) superbly articulated the issue in their guide for assessing strategic training efforts in 2004: "One of the most important management challenges facing federal agencies is the need to transform their cultures to help change the way that government does business in the 21st century. Federal agencies must continue to build their fundamental management capabilities in order to effectively address the nation's most pressing priorities and take advantage of emerging opportunities. To accomplish this undertaking, agencies will need to invest resources, including time and money, to ensure that employees have the information, skills and competencies they need to work effectively in a rapidly changing and complex environment. This includes investments in training and developing employees as part of an agency's overall effort to achieve cost-effective and timely results."1 While problems occur at all stages of the training cycle and affect the training quality and output, problems that occur during the planning phase often have the most profound effects. If issues are not addressed during this phase, they typically cannot be remedied without completely revamping a large portion of the training system or the entire training program, leading to lost time, decreased operational capacity and unnecessary expenditures. Problems in the planning phase abound but most typically stem from the lack of a Functional Area Analysis (FAA) being performed (we will thoroughly discuss the FAA and all of its facets in subsequent newsletter articles). When an organization fails to complete an analysis before building a program or sending their officers off to training with an outside source, they don't have answers to basic yet critical questions and as a consequence, curriculum and programs of instruction (POI) are not based on identifiable need. Specifically, they lack the following key pieces of information:

Overview of the Planning Phase The planning phase of the training cycle is the most overlooked and underrated of all of the cycles. The planning phase is also, some would argue, the most complex of all of the phases due to the workload and comprehensive understanding requirements to perform correctly. The planning phase includes (but is not limited to) the following (not necessarily in order):

Concept of Operations A Concept of Operations (CONOPS) is a graphical statement that clearly and concisely expresses what the agency head or commander intends to accomplish and how resources will be allocated. This document provides solid guidance for commanders and team leaders responsible for building the capabilities required to meet the CONOPS. Communicating Intent Anyone from the military community understands "commander's intent." Many agencies throughout the SWAT community also issue a commander's intent prior to conducting live operations. A Commander's Intent is either a verbal or graphical statement defining the "end state" desired by the commander or agency head. Commander's intent continues to be a major topic of discussion within the military and tactical communities and is also a commonly researched issue; see the following for some examples:

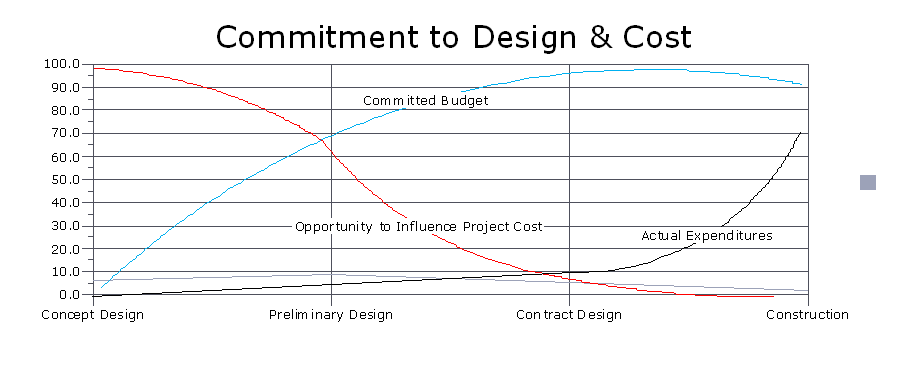

Much of the discussion about commander's intent centers on ideal length, process, and of course, the content of the statement. The discussion on content, more specifically, is whether or not "method" should be included. There is never doubt cast on the need to include "purpose" and "end state". For our purposes here, let's say that Intent = Purpose + End state. Utilizing this definition we will move the discussion on commander's intent away from the level of prepping for an operation to prepping to build team capabilities. To begin any FAA we need to start with direction from the agency head that says, "I want the team to be able to accomplish ________ through ________." The commander's reference will be on missions, not individual tasks. This must be communicated with the team commander(s) and team leaders(s) who will be responsible for developing mission essential tasks for the missions identified by the agency head, and subsequently, collective team and individual tasks. Once these tasks are defined, the FAA development team must define standards for each task. Meanwhile, if using a top-down, bottom-up approach for the FAA (discussed in detail in subsequent newsletters), the agency head/commander(s) will be reviewing strategic response plans from the local level up to the national level to provide the FAA team guidance on conditions. Whether or not these plans shed specific conditional light, the FAA team should be thinking, "worst operational scenarios" to develop guidance on conditions. Initial Evaluation of Design and Cost Under our current economic climate and into the foreseeable future, agency budgets are extremely tight. We must ensure that every dollar spent on training (and every other function within the agency) is diligent and leads to real results. Developing a new program without utilizing a full Capabilities Based Assessment (CBA), beginning with a Functional Area Analysis (FAA) typically results in wasted funds and resources, and continual program changes through after-the-fact evaluation methods. A proper CBA identifies costs and challenges at the earliest stages of the process when the commitment to cost and design is at the lowest point, allowing for greater planning accuracy and reduced expenses.

As the chart above displays, the largest opportunity to influence project design and cost comes during the concept phase. Like grant applications and white paper proposals, a training plan will typically always begin with a statement of need that clearly articulates the existing or the perceived problem. Various data sources should be accessed to define the needs in clear terms. Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) data, for instance, would be commonly drawn upon to establish the need for a specialized unit (such as narcotics, SWAT or violent crimes). In-house data about personnel performance or emerging trends may be utilized to articulate a need addressed by a training solution. Various inputs will be required to conduct a comprehensive FAA. Depending on the scope, there needs to be input from cost estimators, project director(s), HR / personnel staff, trainers, and technical subject matter experts (SMEs) and other personnel involved in the process. STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT When we begin to analyze "why" we train it becomes obvious that perspectives and motivation for training vary and differ between the stakeholders involved. A stakeholder, according to Merriam-Webster, is "One who is involved in or affected by a course of action." Stakeholders invest something in hope of a return greater than their investment. In a single training event attended by one officer from a certain agency, we may find that the end-user attends training to build knowledge or skills, but his immediate supervisor approved the training to reward past performance, while the agency head approved the training to reduce the risk to the agency through a certification process offered by the training. If the notion that training has multiple constituencies or stakeholders whose needs, wants, requirements, and preferences must be taken into account is accepted, it should also be accepted that the only effective way of doing so is to take all of them into account during the design, development and delivery of the training. Anything else is bound to come up short during the evaluation phase (which should be utilized as the basis to form decisions on follow-on training). If the value of the training cannot be made clear and compelling to every one of the stakeholders, the chances that the training will have long-term success will be drastically diminished. Stakeholder involvement in the planning process is particularly important for law enforcement agencies because they operate in a complex political and legal environment. Key stakeholders should be included in the planning phase and an up-front agreement should be reached on the definition of success and its measurement. The following table represents potential investments and expected returns of individual stakeholders involved with a law enforcement-training program. The expected return, as mentioned above, will vary for individual-to-individual and agency-to-agency. Additionally, the investments will vary as much as the expected returns.

Many of the return measures listed are subjective and cannot be empirically measured. Some of the objective measurements are costly and complicated. Herein lays a major problem…how do we accurately and meaningfully measure the return of the training? TRAINING ROI OVERVIEW There is little doubt that the only reason some law enforcement jurisdictions train is because the training is a requirement driven by liability reduction-if the agency spends some money on the front end, it will cost them less on the back end. Training that reduces errors and mistakes, is a solution to a performance problem, and in this case, in advance of a need. It would stand to reason then that agencies, regardless of their reasoning for training, perform a thorough and educated risk and cost benefit analysis prior to making the decision to send their staff to training to ensure they are receiving a Return on their Investment (ROI). Before committing to provide training, an agency needs to take into account the potential costs and anticipated benefits of the program. Expected costs of training to consider include development costs, direct implementation costs, indirect implementation costs (overhead), compensation for participants (including potential holiday pay and/or overtime costs) and lost productivity or costs of backfilling positions. Anticipated benefits of training include increased productivity, improved capability, improved quality, reduced errors and liability reduction, and time and resource savings. However, without performing a thorough FAA during the planning phase, an FNA and a FSA (discussed in subsequent articles), the ROI measurement is going to be less than accurate. As demonstrated with the DHS example in a previous article, better data is required in every stage of the training cycle to receive a true and accurate depiction of the agency's return on their investment. Training, like all other functions within a law enforcement organization, must compete for resources. General budgets for law enforcement agencies are tighter than they have been since most of us can remember. Unfortunately, training is always on the short list of line items to be cut from the budget when times are tight. One reason that training is so easy to cut when competing against other resources within the agency may be that, under the current model most agencies use, with few exceptions, there is not a tangible measurement for the effectiveness of training. Agencies rarely see a true ROI in measureable terms because they lack the data required throughout the training cycle. Resources for all functions within law enforcement agencies must be allocated BEFORE the function is completed or obtained. Training is no different. From this it follows that resource allocation decisions must be made BEFORE the resources can be expended. Consequently, from the budgeting perspective, the decision to send an officer to training based upon the expected result of the training must be made BEFORE the training is conducted, not after. This can only be accomplished with thorough analysis at the planning stage and evaluation at every other stage of the training cycle. Chadd Harbaugh 1 Human Capital - A guide for Assessing Strategic Training and Development Efforts in the Federal Government" GAO-04-546G, March, 2004, pp. i |